- Home

- Willem Anker

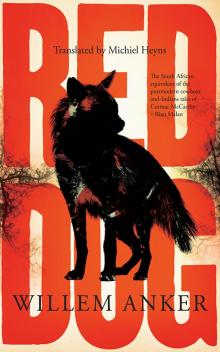

Red Dog

Red Dog Read online

Willem Anker

RED DOG

A Frontier Novel

Translated by Michiel Heyns

KWELA BOOKS

For Christine

Wat sou hulle makeer het, daardie brakke?

om weg te dros uit gawe buurte

– Peter Blum

What could have possessed them, those curs?

to stray from charming neighbourhoods

1761 – 1798

1

Come and see! The lizard on the rock, white ant in its beak. Its jaws start churning. It surveys its surroundings, all along the kloof. Its chomping subsides, its eyeballs roll. The colour of its head and forepaws proclaims its readiness to mate. It displays its red-brown back and ruff. It looks up, swivels its neck to the right. The blue skin of its neck strains and stretches.

See, behind the crag lizard I arise from the rock. I dust my hat, light my pipe. Behold me: I am the legend Coenraad de Buys. Come, let me contaminate you, my reader of tainted stock. If you read this, you see what I see. And I see everything. I am of all time, I am immortal. Do not call me soul. I have a multitude of names. Call me rather Coenraad, or Coen if you are my mother or sister. Pen me down as De Buijs, De Buys, Buys or Buis, just as you see fit. Call me King of the Bastards, Khula, Kadisha, Moro, Diphafa or Kgowe. I am all of them. I am omnipresent. I am Omni-Buys. You will find me in many embodiments. You will come across me as itinerant farmer and anthropologist, rebel and historian. I am a vagabond, a book-bibber, a smuggler, lover and naturalist. I manifest as hunter, bigamist, orator, pillager, patriot, stone-shagger. I am a warrior and a liar; I am a scoundrel and a teller of my own tale. I am going to blind you and bewilder you with my incarnations, with my omnipotent gaze. I am a bird of passage, I am the wind beneath your wings. Stroke the small of my back and you will know I am no angel. I know you well. I know you can’t look away.

May I bewhisper you further? The little hairs in your ear vibrate as my breath comes closer. Migrate with me through human memory, over the unmarked dusty wastes as far as the primal footprint, the first built fire, the troop of ape-like creatures heaving erect in the grasslands. Hear the feet stamping in the caves. See the half-human animals scratching and painting on rock faces, how they trace the trajectories from animal to human, voyages between hand and paw, snout and nose, transitions to the other side.

How far are you prepared to follow in my footsteps? Have you taken fright already? Behold the scars of my passage, the marks of my skin on mother earth. Note well: My hide is this dust and sand. Hear me in every footfall, every hoof-fall. See me reflected in every eye gazing into a fire: I am both mark and mirror. I am of this land, bred from stone.

See, the crag lizard swallows the termite, minutely adjusts its foot, scarcely skims the soil. Listen, history is starting to quake, the dust of forgotten battles and unrecorded deaths is shaken up, quivering under the seething surface.

Rush headlong with me in the frantic flight of time to where the hunters and diggers of roots are shouldered aside by herdsmen and tillers of the land. Onward, through eras of wandering and settlement. Hurry past seafarers planting crosses in their wake. Skim past shipwrecks named for saints, smashed to smithereens on the rude rock of Good Hope. Come wade with me through the rivers of blood: pulsing from noses during dances, spurting from bodies, pouring down hafts and blades of wood and iron, later from bullet wounds, primordially from the wombs of mothers, from hymens and umbilical cords; all the blood always slurped back into the soil.

As through the spiral in the barrel of a gun, more rapidly with every rotation: Streak over hills and dales and Company’s Gardens, over the land, this dumping ground for northern brigands and heretics. Skim along over the cries and sighs of animals and humans. Fly over the importation of slaves and then the importation of horses, over the bones of the Strandloper and the remains of Van Riebeeck’s midday meal, over forts called castles here, over the first Dutch Reformed sermons, the first sugar, the first brandy, over the blood, over riot and revolution, over drawn-and-quartered rebels and black holes of incarceration. Flash over wars and Christians and Hottentots and Caffres and Huguenots and Dutch courage and chicanery and pox and Groot Constantia and the Great Fish, over rivers that erode and borders that overgrow. What are you looking for here? Do you know why you’re looking for me? What are you going to do when you find me? Go on, go kneel by any carcase and see the flies cluster like a cosmos opening into bloom; see! This here ground obliterates and digests. It slurps up history and boils it down to nothing.

Listen, the songs of the land resound over it all. Hear the songs of men, the songs of the veldt, the skirling and screaming. Just listen to the beat on metal and sticks and stones and oxhide, on bellies and hoofs, on stoneware from the earth. All over this wretched earth the roaring and bellowing, the yowling and yelping. The claps and the cracks. So loud, so quiet. So delicately the salamander places its foot, I could swear it can smell the blood in the soil.

Perhaps you feel safer in the back rooms of museums? I am the feeler of the fish moth in every archive. I have access to every page. I feed as I read. So let us riffle through the names on maps of new rivers and new mountains and lines of longitude and lines of latitude and missionaries and old gods and a new nailed-down god and churches and caves and the cradle of mankind. Speed-read through murder and mayhem and scouts and pioneers and rebels and vagabonds and clashes and punitive expeditions and slave rebellions and cattle rustlers and colonisers and corpses, all the corpses. Verily, even at this distance the echoing blows and gunshots, yes, even from the pages of blushing historians. I have seen it all, read every word. I forget nothing and forgive mighty little.

Come and see! calls my voice in this semi-wilderness. Come see the land break open its seals for you. Here where the shepherds shall have no way to flee, nor the principal of the flock to escape. Here where the Milky Way is spread out like the spine of a half-dead dun horse deliriously holding up the heavens over De Lange Cloof. Plains with flakes of rock and sand sometimes as red as old blood and sometimes as white as bone. In the north and the south serried mountains lie like petrified elephants heaving themselves out of the earth and then slumping back halfway and over centuries are once again buried under bush and stone. You can still see the wrinkles of their shoulders, the old necks and flaccid trunks, stretched out, spent, for miles across the landscape, but when you think you can hear them sigh, it’s only the wind. The mountain slopes are lush, the kloofs wet and overgrown with ferns. The rock ridges gash open out of the green hide of the hills. The people build their houses near the rivers and name their farms after the rivers. The farms lie in a row, cattle territory at the far end of the kloof, a world of sitting and contemplation. If you get up and look around you, you can see your whole farm and from afar you can espy your damn neighbour approaching.

If you look carefully, you’ll see the little house of stacked stone and bulrushes. If you listen carefully, you’ll hear the people in the house bustling around the dying body of a father. The lizard you will not see again. It was rapt at sunset by the hawk.

See, I’m standing in the doorway. I am eight years old. I look like my mother. My father is lying on the narrow cot. His back arches like a Bushman bow, then he sinks back again. Maybe some creature bit him in the veldt. Perhaps he chewed the wrong leaf. A few days ago he came home and complained and nobody took any notice. My mother scolded him for a laggard and lazybones. He went and lay down and never again spoke a straight sentence and never again got up. In the kloofs jackals and hungry dogs are calling. Shreds of candlelight bob up and down in the washbasin. My sister sits down next to me, her fingers form shadow figures against the wall. My father’s hands scrabble at his stomach. A bellowing, then the drawing up of the legs.

Oh God! My Lord

God.

My mother Christina rebukes her husband; he falls silent, mutters something inaudible. Mother instructs us to carry him out of the bedroom cot and all and place him by the hearth. She oversees our doing, walks out. I go and stand by her side; she pays me no heed. My eldest brother comes into the house with a headless chicken, slits open the belly and presses the spread-eagled fowl onto his stepfather’s chest to draw out the fever. Father once again calls to our God born in deserts and wars and thrusts the fowl from him. Mother commands another flayed-open hen. This time the bleeding warmth is tolerated for longer. I sit in the corner and peep from under a heap of hides how through the night chicken after chicken is pressed to the cropped-up chest. With the first glimmering of dawn I help Mother to plaster his chest with cow dung. I spread the steaming dung, feel the tremors under the skin.

Don’t touch me! Father bellows.

I step back.

Stop your nonsense, says Mother.

Father is silent.

They slaughter a goat and drape the guts over the body. My sister brings water. Mother goes to stand in the yard. My brothers and I rinse the blood from the dung floor, massacre chickens and stoke the fire in the hearth. Father’s convulsions drive our little lot like a troop of sleepwalkers until with a sudden starting up and last spasm as if the limbs wanted to tear themselves free of his innards, he sighs and dies. I hunker by the fire and regard my father: Jan de Buys, Jean du Buis the Third, grandson of a Huguenot, son of a rich Boland farmer. His death, like his life, small and meek.

Come, let us dig up my parents’ remains from the archives: At age twenty-two father marries Christina Scheepers, twice-widowed, eight years older than he. Grandfather de Buys, the old scoundrel, sends Father packing with a wagon and a few over-the-hill oxen. The couple – and Mother’s five children by her previous husbands – hit the road. They drive their little cluster of cattle until they pitch their tent on a deserted piece of land next to a random stream. Husband and wife and children and Hottentots build a house of reeds and grass and clay, and live there while Christina bears two daughters who hardly show their little wet heads between her legs before dying and are buried without names in holes that are covered up and not marked and leave absolutely no scar on the face of the earth. Father and Mother do not know the territory and the cattle die of the poisonous grass and bulbs and a drought claims the rest of the herd. They wander through De Lange Cloof and by Mother’s account I am born in the year 1761 on Wagenboomsrivier, the farm of one Scheepers. We roam further afield. Thorn trees and ferns grow in the kloofs and leopards dwell on the slopes and we squat with family and acquaintances. A year later Father signs for the quitrent farm Ezeljacht in the Upper Lange Cloof, where the pasturage is more abundant. Father and the older sons and the Hottentots build a house. A reed partition divides the interior into two rooms. The bulrush roof trails on the ground. Christina bears more children of whom two sons and two daughters survive.

When the rest of the house is stunned to sleep by shock, I stay sitting and looking at my father while the fire in the hearth slowly fades. That morning I am eight and overwhelmed; every now and again I get up and feel him getting colder. Today, in my all-seeing, I look back. I see my beloved father lying there in his house like the houses of other migrant farmers. Habitations of which purse-lipped English travellers will one day write that they look more like the lairs of animals than the homes of human beings. At the time of his death he’s long since been totally routed by the woman and her ten children. A poor man, his estate barely seven hundred rix-dollars. A lifelong, very gradual and inexorable surrender. A fatal politeness and compliancy that would have rendered even the feeblest resistance to the poison from the veldt too self-assertive for him.

By late morning Mother is assigning tasks like every blessed day. The bustling runs its course around the body, displayed on the cot. On the floor lies a little posy of heather that somebody placed on the body and that fell down and that nobody picked up again.

I try playing with my brothers and sisters. My brother with the long arms carries me around on his shoulders. My sisters want to hold me and cry. The younger brothers and sisters seek comfort from me. I don’t know how to comfort. I slap my youngest brother when he starts crying and then he bawls more loudly. I go and hide against the house, underneath the window. Mother is standing by the body with her arms folded. She sees me, walks to the window and looks straight through me and pushes the wooden shutter back into the window opening. I walk around the house and enter by the door. Mother is standing next to the body again. I press my head into the dark and soft pleats of her dress. She places a hand on my shoulder. The hand moves over my back and rubs up and down and presses me close and then drops to her side. I look up at her and she says something that I forget instantly and I walk to the river and strip shreds of bark from the trees and watch them floating away on the water and throw stones in their wake. By afternoon two of my sisters come looking for me and press me to them and start wailing again. The sun shifts; I wander around the yard. My brothers are all busy and grumpy and nobody has a job for me and nobody wants to play. I inspan my knucklebone oxen on the dung floor.

Get out from under my feet, she says.

I’ll be good, Mother.

Go and play outside. You can’t be a nuisance in the veldt.

I’ll sit still, Mother.

Outside! There’s nothing there for you to break.

The sun sets. The moon rises. I lie between my brothers and sisters in the front room and listen to our mother snoring in the bedroom. I hold the sister closest to me as tight as I can. Until she wakes up and knees me away and turns over.

At the funeral I watch them weeping. Something barks me awake in the night. I get up from the heap of over-familiar bodies slumped on top of one another like a litter of backyard kittens. I walk away, I stand still. The house is a dull smudge against the stars. I turn away, walk on, turn around and look at the house again to see if anybody is coming to look for me. If anybody should rush out of the house now, I’ll run away, but not as fast as I can. One of my older brothers will catch up with me and plough me into the dust and drag me home and flay me.

I walk to the house of my half-sister Geertruy, my godmother Geertruy and her new husband, David Senekal, at the far end of the farm, and I don’t look back again. The moon is hanging too heavily; the treetops can barely hold it up. The farm is big, more than three thousand morgen, and on this night much bigger. It is cold.

I stand still, look around me. Geertruy is not far away. If I go and knock there in the middle of the night, she’ll carry on about it. Mother is not far. If I go back there, my sisters will wake up and comfort me.

I sit down against a red rock that looms up from the scrub like a gravid hippopotamus. I dig next to the rock. The soil soon becomes friable; I dig further. I curl up in my hole against the rock lying hard behind me and of which I cannot imagine the nether end. I scrabble soil all over me. I press it hard against me like the back of my sister. Everywhere herds and flocks and swarms are calling to one another; they warn and threaten and lure. Once I see steam rising out of a pair of nostrils against the pale moon and then the eyes glittering in the bush and then nothing except wings breaking branches. The moon glides past and reflects against the rock above me and spills out onto the ground in front of me. The little I can see in the meagre reflection of the distant light tells me I am safe, and beyond that, I tell myself, everything I hear is only the wind in the brushwood.

I wait by the side of the yard until the people start stirring. I knock at the door. Geertruy opens and takes me inside and spreads a straw mat in front of the fire in the living room.

A few months later Mother marries Jacob Senekal, the young gallows-bait brother of Geertruy’s David. Mother is forty-eight and Jacob twenty-eight, but Mother is a pretty woman with a good many teeth for her age. By candlelight she looks younger than Geertruy. Two years later our grieving mother buries Li’l Jacob as well. The clods have hardly cov

ered the coffin when a next Jacob arises, one Helbeck, who comes to share her bed and brood at Ezeljacht.

I’ve not been away from home for long. I have trouble sleeping in the strange house. I cuddle up to the kaross, think back to the bodies of my brothers and sisters who kept me snug on such nights. I steal into the other room where the family sleeps and crawl in next to Geertruy and David and their child. Dumb-dick David chases me out of the house. The next morning after we’ve consumed our daily eggs and griddlecake in silence, Geertruy takes me aside and explains the sleeping arrangements here. She presses me to her and holds me like that and I don’t let go and then she takes my arms from her. She goes into the house and gives the baby breast and when that dog-dick David catches me peeping, he gives me a thrashing and the next day the piece of putrid pig’s pizzle wallops me once more.

Geertruy is sitting with me under the tree, so old and gnarled nobody knows any more what kind of a tree it is. It is so tall, I’ve never managed to climb more than halfway up it. On Tuesday mornings she teaches me to write in Dutch. It is hot, but I draw the kaross closer around me. Last night I dreamt. I was against the red rock again, I covered myself with soil again. Then I sank away, the soil covered my face, poured into my nose and mouth. In the dream I suffocated. I woke up cold and wet and hurt. I opened the door, coaxed one of the yard dogs inside. The dog settled on my kaross; I snuggled up against him.

The dog is called Ore, for his large flapping ears. He is sitting next to me under the tree. I am still cold. Geertruy is teaching me about zijn and hebben, being and having.

Ik ben, zij is, het is, jullie zijn, she says, I am, she is, it is, you are. Wij zijn. Zij zijn. We are. They are.

She waits for me to recite the list. I look at the white sunlight beyond the shade of the tree. The soil is quaking with heat.

Red Dog

Red Dog